Back in November, I wrote about how women have shaped the world of puzzles, both in the past and in the present.

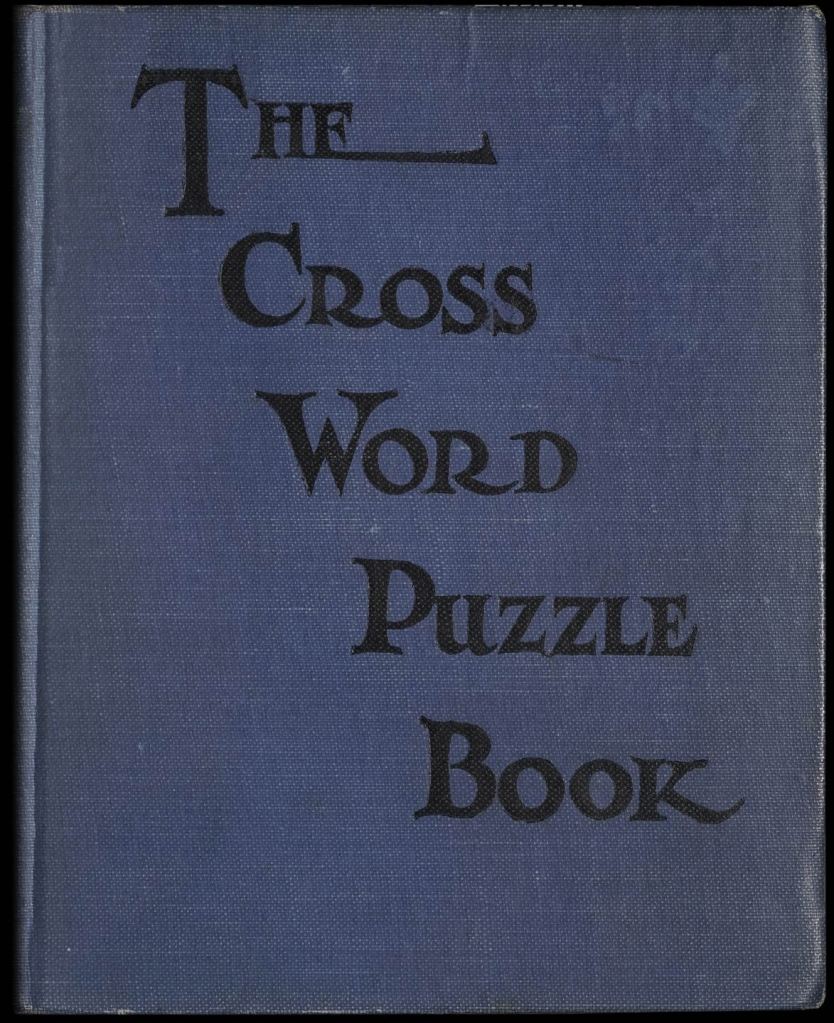

One of the first women I mentioned was Richard Simon’s aunt. According to the lore of Simon & Schuster, she was the one who inspired Simon to publish a limited release book — the first crossword puzzle book — that launched their publishing empire.

While I was writing that post, I spent a little time researching, and I never came across her actual name. Everywhere I looked, it was simply Richard Simon’s aunt.

And that question festered in my brain for a while.

So, one day, I reached out to Simon & Schuster directly, asking for more information on Simon’s influential aunt. I heard back from Hannah Brattesani, their backlist manager, who not only volunteered to comb through the various company histories, but also suggested a book for my research (Turning the Pages by Peter Schwed).

While Hannah investigated from the S&S side of things, I decided to pursue what was publicly available about the Simon family tree. Perhaps I could look up his aunt directly and find a name that way.

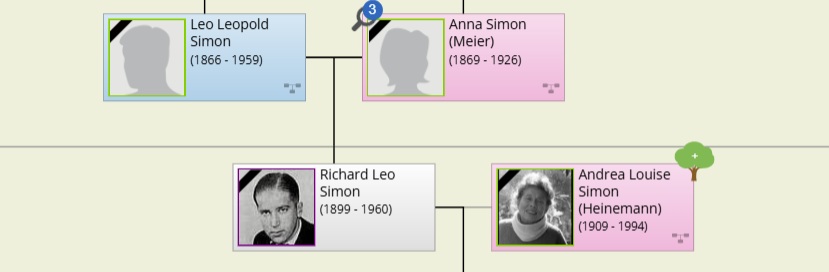

I found that Richard L. Simon was the son of Leo Leopold Simon and Anna Simon (nee Mayer). Leo apparently only had brothers, while Anna’s only sister, Julia, died young.

Okay, that was a dead-end. Ah! But what about women who married into the family?

Anna’s brother Max Reinhard Meyer married a woman named Harriet and Leo’s brother Alfred Leopold Simon married a woman named Hedwig.

So we have two possibilities, but nothing concrete tying either of them to crosswords or S&S’s early days.

I heard back from Hannah, who unfortunately came up empty while searching the S&S archives. The closest we got was a reference from a book celebrating S&S’s 75th anniversary, mentioning “Mr. Simon’s strong-willed aunt.”

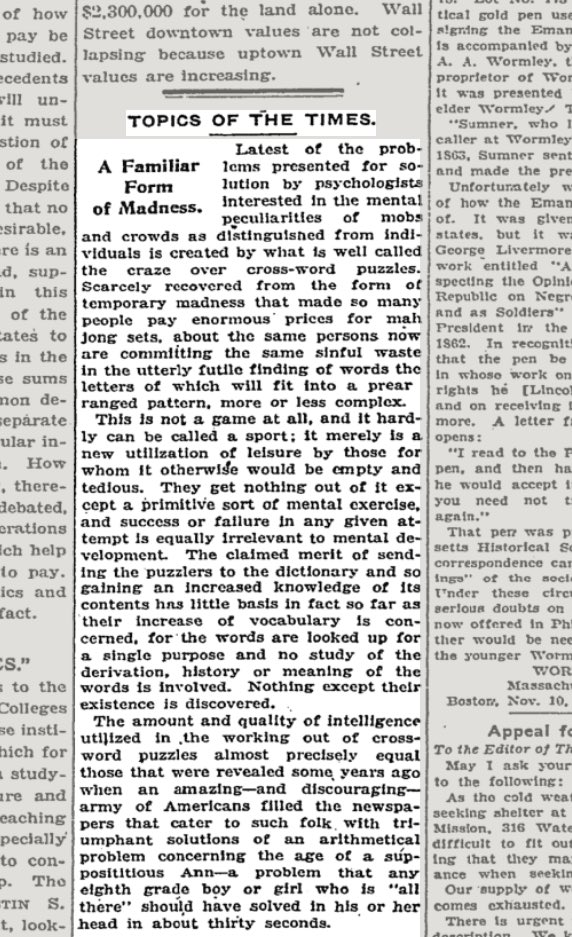

Before I continue, I want to take a moment to ponder all the different permutations of the Richard Simon’s aunt story. For a casual anecdote that adds charm to a business’s first success story, there are a surprising number of variations.

In Turning the Pages and The Centenary of the Crossword, the story goes that Dick Simon had been asked by his aunt for a little help with a crossword puzzle to which she had become addicted. She considered there should be a book of these published.

In an article in Pressreader, she asked him where she could buy a book of crosswords like the ones in her favorite newspaper.

In What’s Gnu?: A History of the Crossword Puzzle by Michelle Arnot, she wants a collection of crossword puzzles for her daughter, an avid fan of the weekly puzzle in The World. In The Crossword Century and Thinking Inside the Box, Simon goes to dinner with his aunt, whose niece was addicted to crosswords.

So the only common threads are Simon, his aunt, and crosswords. Sometimes it’s for her (described as “puzzle mad” or, as we’ve already seen, “strong-willed”), or her daughter, or her niece, or a friend. Sometimes he notices her solving crosswords, sometimes she tells him. Sometimes it’s at her house, or over tea, or at dinner.

Sure, lots of anecdotes evolve over the decades. Any story from your family probably has a number of variations, depending on who tells the tale.

But it’s fascinating that such a fundamental moment in S&S’s history doesn’t really have an official version as part of the narrative.

So, we have Richard Simon, his aunt, and crosswords. Those were the common threads.

And it was the third one in that list that finally led me to her name. Not crosswords per se, but crossword history.

There are several marvelous books about the history of crosswords — I’ll post a list of my sources at the bottom of today’s post — and wouldn’t you know it, several of them include a name for Simon’s aunt!

Well, not a name. A nickname.

Wixie.

Yes, it’s somehow so brilliantly fitting that the woman who launched crossword publishing (for herself, a daughter, a niece, whomever) would have a whimsical nickname like that.

Aunt Wixie.

As it turns out, this nickname was sort of an open secret in the annals of crossword history and I’d managed to miss it in my previous searches across the internet. My grand mystery would have been solved much faster if I’d simply asked some of my fellow puzzlers and puzzle historians.

But I wasn’t disappointed to learn that I was late to the table. On the contrary, I was excited to add “Wixie” to the search parameters and see what I came up with.

A few more online sources were revealed, but sadly, not much else about Aunt Wixie herself.

Now, sharp-eyed readers, you’ve probably come to the same conclusion I did at this point.

Thinking back to what I’d learned about the Simon family tree, I had two possible aunts who had married into the family who could be our crossword-loving inspiration.

One was Harriet and one was Hedwig.

It seems like a natural conclusion that Aunt Wixie and Aunt Hedwig would be one and the same. But none of the sources, paper or digital, ever mentioned her real name.

I could’ve called it here, and written my blog post, and gone on my merry way.

But I wanted that last piece of puzzle that I could definitively point to and say, this, this is her.

In all those Google Books links and online articles, there was one source I couldn’t view publicly, because it was behind a paywall. Naturally, it was also the oldest source I could find online that came up using “Wixie” as a keyword: an issue of Publisher’s Weekly from 1954.

And I could read it… for a fee.

You may find it funny that I balked at spending twenty bucks for access to an article. But I did. I mean, none of the other sources told me more than her nickname and some variation on the crossword book creation myth. Would this one be any different?

As it turns out, yes, yes it would.

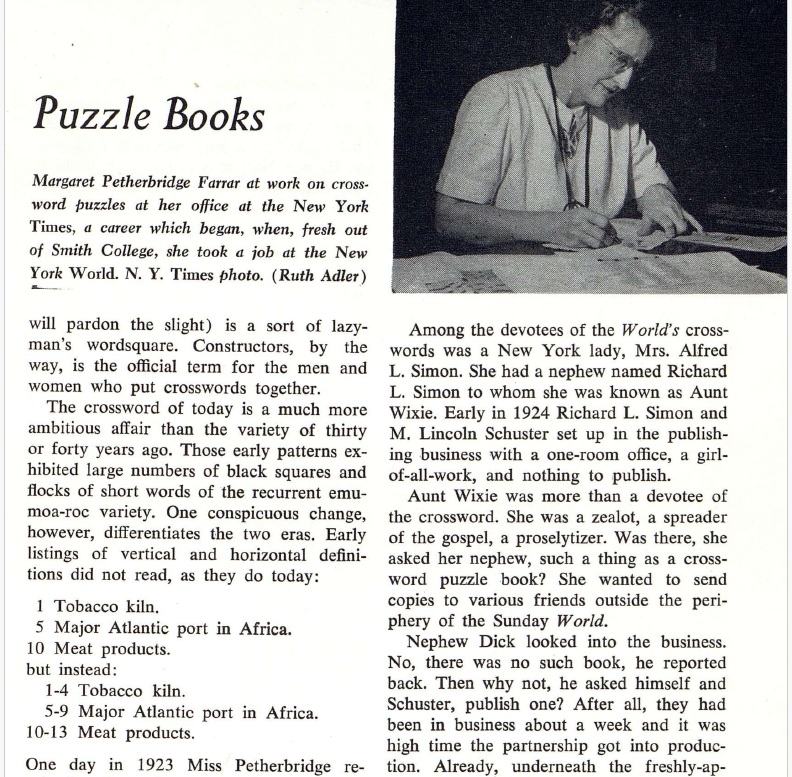

From the writeup in Publisher’s Weekly:

Among the devotees of the World’s crosswords was a New York Lady, Mrs. Alfred L. Simon. She had a nephew named Richard L. Simon to whom she was known as Aunt Wixie.

It is so perfectly typical that the smoking gun in my search for Richard Simon’s aunt’s name STILL doesn’t directly mention her by name, using her husband’s name instead. What an insanely fitting denouement.

Nonetheless, I finally had the connective tissue to tie the whole story together. From my deep dive into the Simon family tree, I knew that Mrs. Alfred L. Simon was none other than Hedwig Simon (nee Meier), our elusive Aunt Wixie.

So what do we know about Hedwig?

Sadly, very little. She was born in Frankfurt Am Main, Regierungsbezirk Darmstadt, HE, Germany on February 27, 1868. She had two children, Robert and Helen (hopefully a puzzle lover like her mother, depending on the story), and she died in May 26, 1932 in Manhattan.

That’s it. Several Hedwig Simons come up when you search the name, but unfortunately, I wasn’t able to find anything else I could verify was truly about Aunt Wixie.

Date of birth. Names of her children. Date of death. That’s all we know.

Oh, we actually do know one other thing.

We know that she, in some way, influenced the creation of the very first crossword puzzle book, helping to launch a literary dynasty that lasts to this very day.

But did she though?

It turns out… there’s an asterisk on the historical record that’s worth mentioning.

There is a chance that this entire story is apocryphal, and the influential hand of Aunt Wixie in Simon & Schuster’s earliest days was not as influential as the story makes it seem.

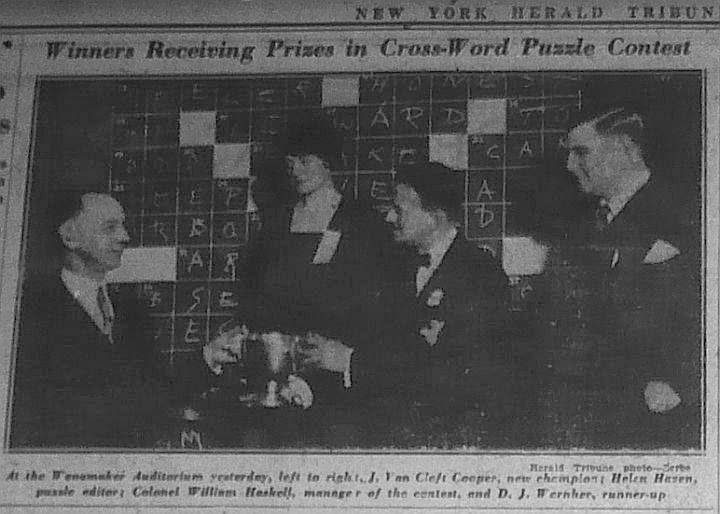

Michelle Arnot reported in her book that Margaret Farrar, first crossword puzzle editor for The New York Times, had her doubts about Aunt Wixie’s role in the creation of S&S’s first crossword book.

In the foreword to Eugene T. Maleska’s 1984 book Across and Down: The Crossword Puzzle World, Farrar herself wrote:

There had never been a book of crosswords and Dick Simon’s aunt had suggested one. (Dick later admitted to me that this was all a joke, even unto the framed memo up on the office wall noting this earth-shaking idea.)

Could Aunt Wixie’s role in the history of crosswords simply be Richard Simon’s invention to help sell crossword books and add some whimsy and down-home family charm to Simon & Schuster’s first of many success story?

Margaret Farrar seemed to think so, and she was one of the most respected names in puzzles.

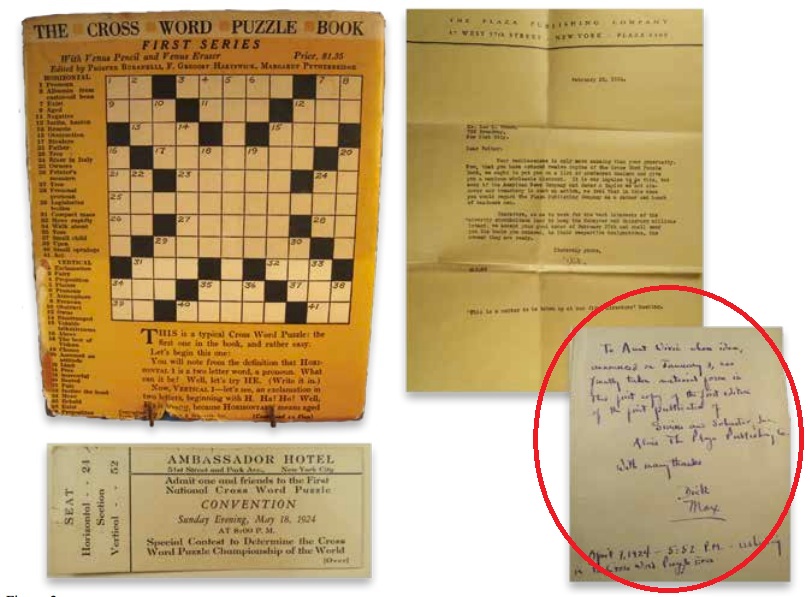

If this IS the case, Simon seemed to go out of his way to sell the story. He had a framed memo on his wall, as Farrar mentioned. He had a presentation copy of the first crossword puzzle book inscribed by both himself and Max Schuster to Aunt Wixie (the note pictured above), which was returned to Richard Simon upon her death, and which now resides in Will Shortz’s private collection.

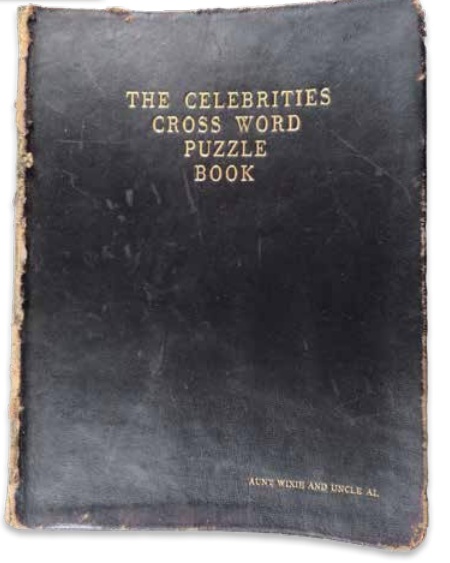

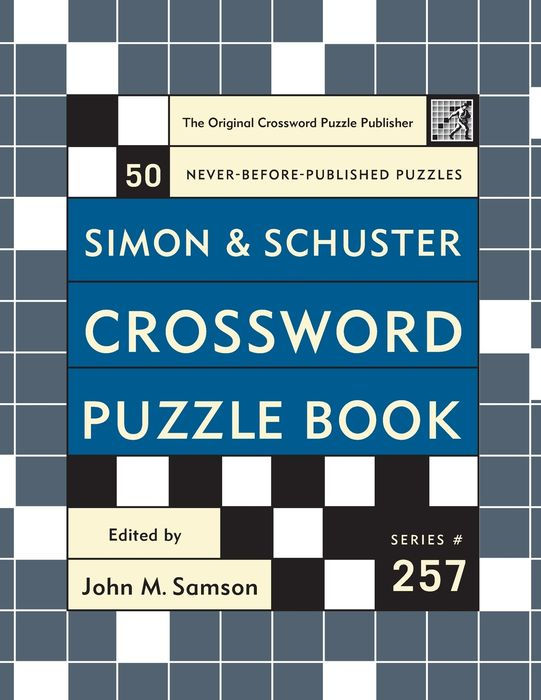

Will’s collection also includes a copy of 1925’s Celebrities’ Cross Word Puzzle Book, a collection by S&S featuring puzzles created by (you guessed it) celebrities. It’s a leatherbound presentation copy specially printed for “Aunt Wixie.”

By the end of 1924, S&S already had four bestselling crossword compilations on the shelves. By the time The Celebrities’ Cross Word Puzzle Book was published in 1925, would Simon still have bothered with perpetuating the Aunt Wixie story, given the runaway success of S&S’s crossword puzzle books?

It seems a tad unnecessary.

The many variations on how Aunt Wixie, Simon, and crosswords influenced that first puzzle book could mean the story was made up, taking on a life of its own as it was shared anecdotally. Or it could mean that it’s true, as many stories from a hundred years ago have variations from being shared over and over again, retold many times. It’s hard to say either way.

I choose to believe that Hedwig Simon was in fact the impetus behind that first book. Maybe it’s naive to want her to be a true crossword enthusiast (or the mother of one, or the aunt of one), and not simply one more corporate invention to sell something to someone.

But I’m okay with that.

I’m happy to have spent this time and energy trying to unearth her name and learn a bit more about her, and I’m hoping that I might have the opportunity in the future to continue learning about her.

And I’m happy that this post, in some small way, might bend search algorithms and lead more people to associate the name Hedwig Simon with Simon & Schuster’s successes.

Narratively, I probably shot myself in the foot a little by putting her name in the title of the blog post. But this entire endeavor has been about learning more about her, learning her name, and it would be the height of selfishness to bury it in hundreds of words of text just for a ta-da moment.

So, in closing, let me just say, thanks Aunt Wixie, and it was nice to meet you, albeit very briefly, Hedwig.

My sincere thanks to Hannah Brattesani of Simon & Schuster, Rebecca Rego Barry of finebooksmagazine.com, and especially Ben Zimmer, who provided several key sources and links (and confirmed that the Publisher’s Weekly was the earliest source on the subject).

Sources:

-Turning the Pages: An Insider’s Story of Simon & Schuster 1924-1984 by Peter Schwed

-What’s Gnu?: A History of the Crossword Puzzle by Michelle Arnot

-The Centenary of the Crossword by John Halpern

-The Crossword Century by Alan Connor

-Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures with Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them by Adrienne Raphel

-Publishers Weekly (April 17, 1954, Volume 165, Issue 16)