Kryptos is one of the great remaining unsolved puzzles.

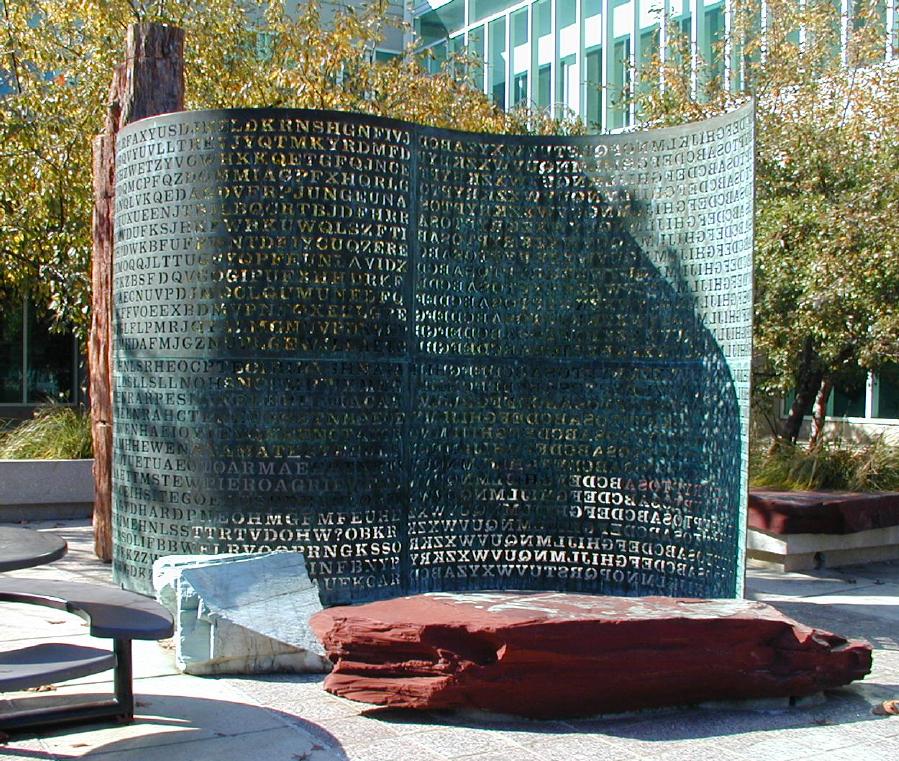

A flowing sculpture made of petrified wood and copper plating, sitting over a small pool of water. That’s what you see when you look at Kryptos.

It was revealed to the world in 1990, coded by former chairman of the CIA’s Cryptographic Center Edward Scheidt, and designed by artist Jim Sanborn. Designed to both challenge and honor the Central Intelligence Agency, for decades Kryptos has proven to be a top-flight brain teaser for codebreakers both professional and amateur.

Of the four distinct sections of the Kryptos puzzle, only three have been solved.

After a decade of silence, a computer scientist named Jim Gillogly announced in 1999 that he had cracked passages 1, 2, and 3 with computer assistance. The CIA then announced that one of their analysts, David Stein, had solved them the year before with pencil and paper. Then in 2013, a Freedom of Information Act request revealed an NSA team had cracked them back in 1993!

A curious game of one-upsmanship, to be sure. Something that foreshadowed what would follow years later…

Unfortunately for puzzle fans, K4 remained unsolved.

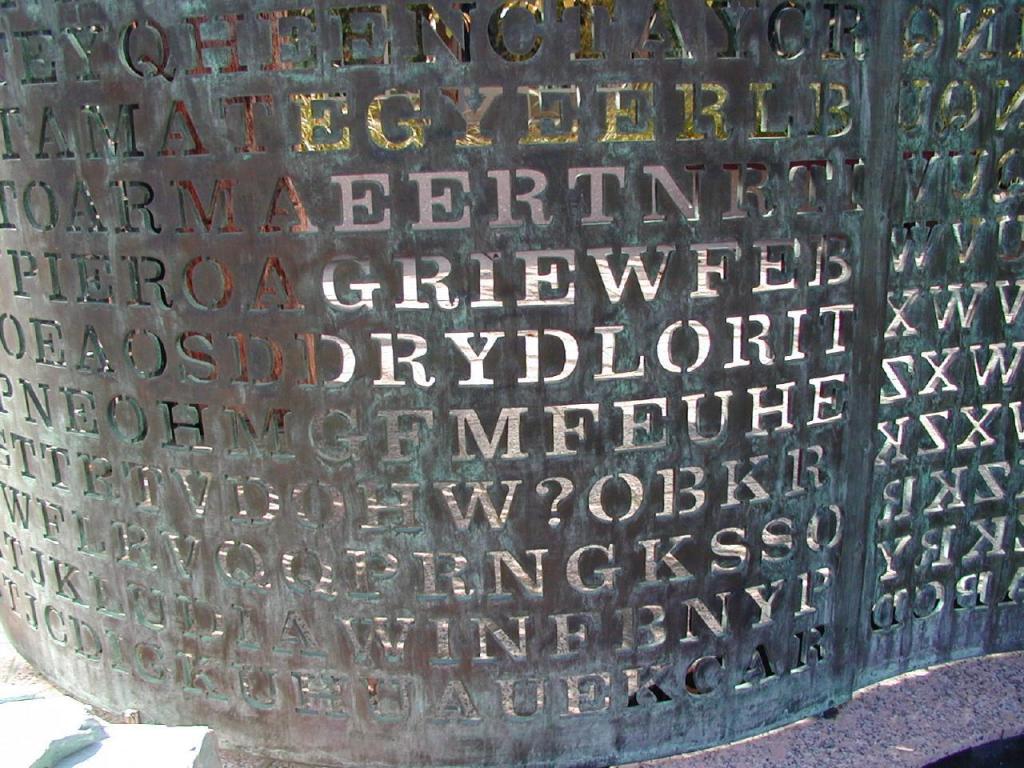

Eventually, Sanborn began offering hints. In 2006, he revealed that letters 64 through 69 in the passage, NYPVTT, decrypt to “Berlin.” In 2014, he revealed that letters 70 through 74, MZFPK, decrypt to “clock.” In 2020, he revealed that letters 26 through 34, QQPRNGKSS, decrypt to “northeast.”

Still, K4 remained unsolved.

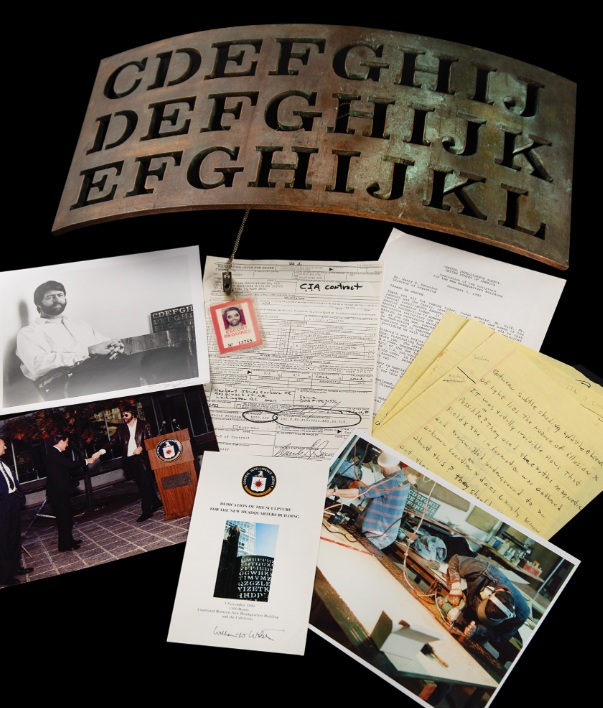

Back in August, I wrote about Sanborn’s impending auction for the solution to the Kryptos puzzle, as Sanborn felt he no longer had “the physical, mental or financial resources” to maintain his role as the keeper of K4’s secret, and wished to hand that responsibility to another.

On November 20th, 2025, the solution to Kryptos sold to an anonymous bidder for $962,500, far above the predicted $300,000 – $500,000 estimate from the auction house.

At the moment, we don’t know if this anonymous bidder will reveal the solution or become the new keeper of the mystery.

You might think that the story of Kryptos would conclude there, for the moment.

But that’s not the case. The auction and its near-million-dollar bid were put into jeopardy by two intrepid investigators and a simple oversight by Sanborn himself.

On September 3rd, not long after I wrote about the upcoming auction, Sanborn received an email with the solved text of K4 from Jarett Kobek and Richard Byrne. They had discovered the solution among Sanborn’s papers at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, after the auction house had mentioned the Smithsonian in their auction announcement.

Kobek and Byrne had discovered Sanborn’s accidental inclusion of the solution in the papers donated to the Smithsonian ten years ago during his treatment for metastatic cancer. “I was not sure how long I would be around and I hastily gathered all of my papers together” for the archives, he said.

Suddenly, the auction was in doubt.

Sanborn confirmed to Kobek and Byrne that they indeed had the correct solution. Later that day, he proposed they both sign non-disclosure agreements in exchange for a portion of the auction’s proceeds. They rejected the offer on the basis that it could make them party to fraud in the auction.

Sanborn reached out to the Smithsonian and got them to block access to his donated materials until the year 2075, to prevent others from following in Kobek and Byrne’s footsteps and further endangering the auction. Meanwhile, lawyers for RR Auction threatened Kobek and Byrne with legal action if they published the text.

Sadly, Kobek and Byrne had been put in an impossible position. They have the solution that diehard Kryptos fans have desired for decades, and the possibility of coercing them into revealing the solution is hardly low. Sanborn’s computer has been hacked repeatedly over the years, and he has been threatened by obsessive fans, even claiming he sleeps with a shotgun just in case.

The auction house did disclose the discovery of K4’s solution to the bidding public, as well as the lockdown of the Sanborn archive at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

All parties waited to see what would transpire.

Still, with all this uncertainty looming, the auction closed with its $900,000+ bid, and thus far, neither the anonymous bidder nor the team of Kobek and Byrne have released the solution.

Byrne and Kobek say they do not plan to release the solution. But they are also not inclined to sign a legally binding document promising not to do so.

I waited to write about this story in the hopes that something would have been resolved in the weeks following the auction’s conclusion. But sadly, K4’s solution — and Kobek and Byrne’s potential roles in revealing it — remain unknown at the time of publishing this post.

Despite all this, the fact remains: Kryptos fans haven’t cracked K4.

But they know of four possible sources to find the solution: the Smithsonian (which is locked down), the anonymous bidder (similarly inaccessible), Sanborn (who has been fending them off for decades) and sadly, Kobek and Byrne, who remain in the crosshairs of the media, lawyers, and Kryptos enthusiasts. The pressure is mounting.

I suppose the best case scenario would be for someone to legitimately crack K4 and release their solution AND method for solving it.

That would free Kobek and Byrne from their burden and potential legal repercussions. That would be the triumph hoped for when Kryptos was conceived. The auction’s validity would remain intact.

Because even if the plaintext solution is revealed and someone reverse-engineers how it was encrypted, it’s a damp squib of an ending. Kryptos wasn’t solved. It wasn’t figured out. It would be a disappointing way for a rollercoaster of story to wrap up.

Sanborn deserves better. Kobek and Byrne deserve better. Kryptos deserves better.

So get cracking, solvers!