Mystery novelist Agatha Christie was an avid surfing enthusiast. Abraham Lincoln is in the National Wrestling Hall of Fame and only suffered a single defeat in 12 years. We wouldn’t have Wi-Fi or Bluetooth without the scientific prowess of actress Hedy Lamarr.

It’s fascinating to learn unexpected facts about iconic figures from history that don’t necessarily jive with their most famous accolades.

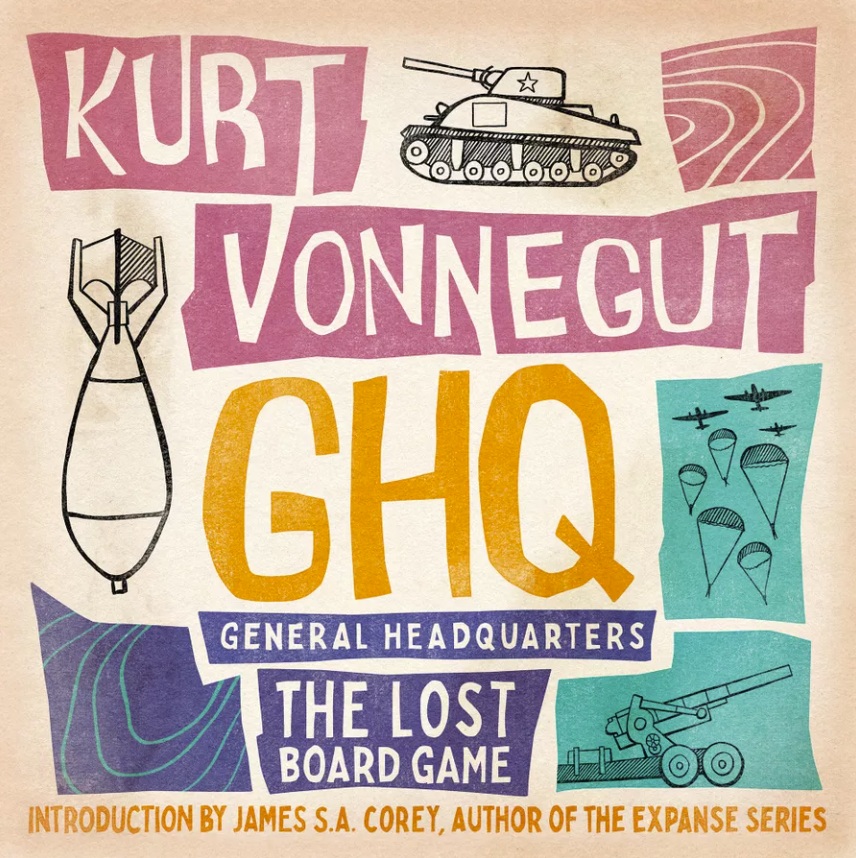

For instance, did you know that celebrated writer Kurt Vonnegut made a board game?

Yes, nearly seventy years ago, after the less than stellar commercial performance of his novel Player Piano, Vonnegut attempted to create a third game to utilize the 8×8 checkerboard as effectively as chess and checkers did.

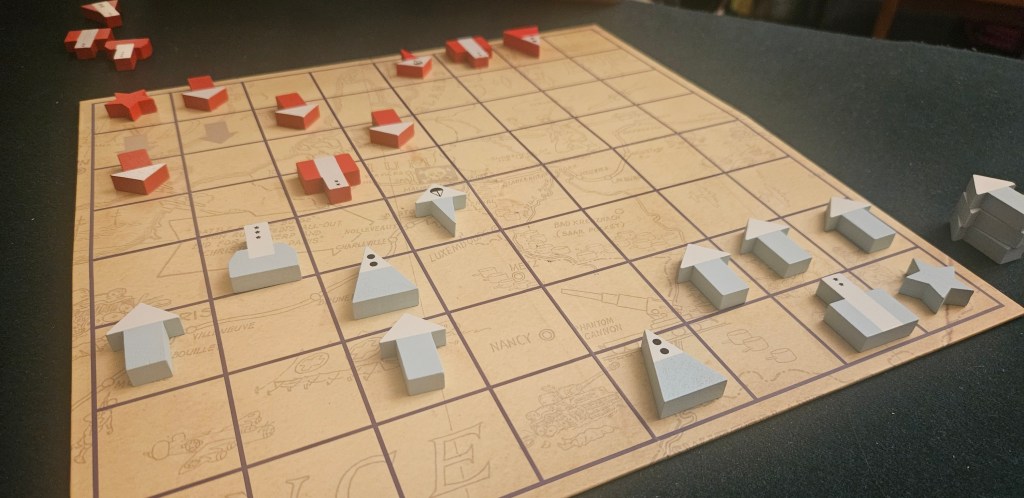

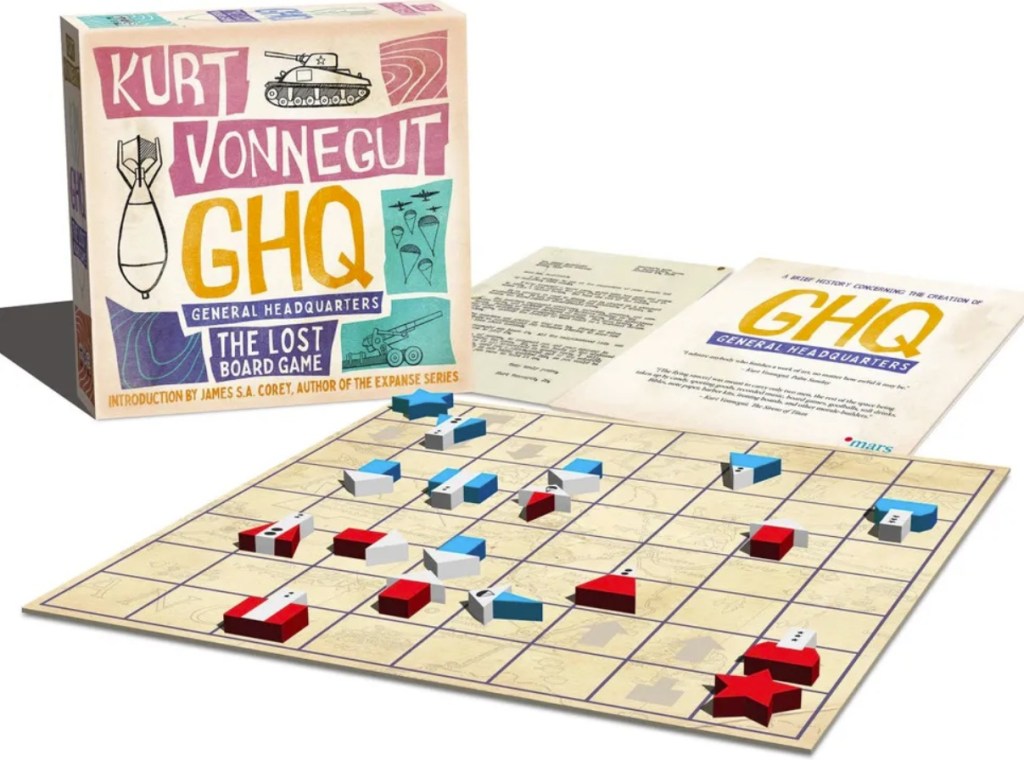

It was called GHQ, short for General Headquarters, and it was a tactical strategy game involving balancing your ground infantry and artillery forces with your airborne forces to capture your enemy’s headquarters.

In 1956, it was downright innovative, mixing wargame mechanics and multiple actions in a single turn. (This is commonplace today, but was quite revolutionary in games for the 1950s.) In today’s board game market, the initial run sold out, and now the game is carried by Barnes & Noble, and I have no doubt it’s performing well.

This would come as a shock to Vonnegut, as the game was rejected by publisher Henry Saalfield of the Saalfield Game Company. Vonnegut put the game away, and as far as his family knows, he never went back to it at all.

That historical context makes the game (and its companion booklet) a wonderful glimpse into Vonnegut as a creative mind.

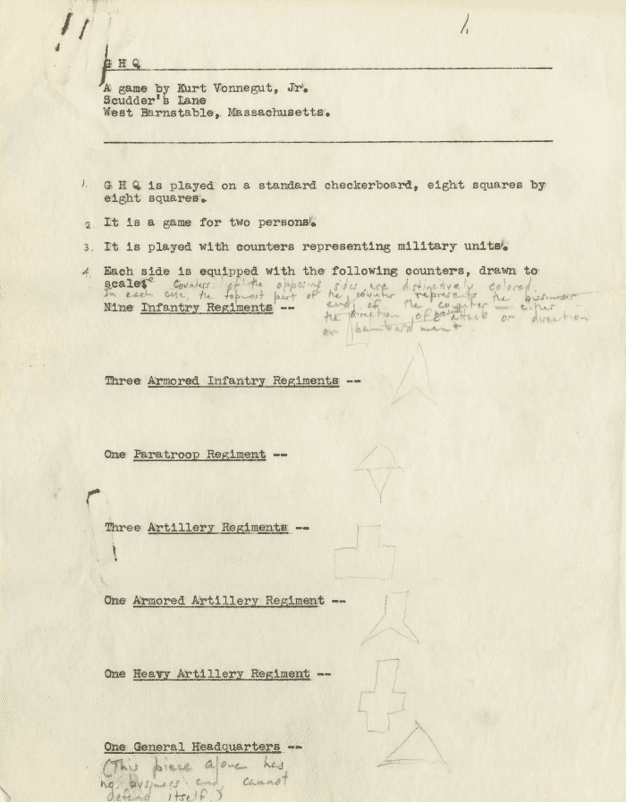

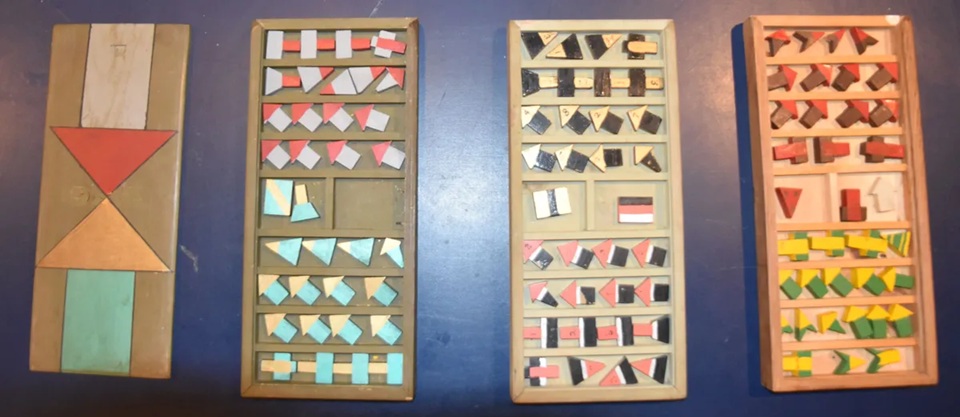

We get his original notes — including rules for the game — as well as photos of the original game pieces from his prototype.

GHQ exists as a fascinating conundrum. How do you reconcile encountering a combat-focused game designed by someone famous for his antiwar sentiments?

A review of the game on Spacebiff had something interesting to say about this:

It’s also so very Vonnegut. Years before Billy Pilgrim manifested as his coping mechanism for the horrors he witnessed in the Ardennes and during the firebombing of Dresden, here he was designing a game that drew on his experience as a spotter for the 106th Infantry Division. It’s a game rooted in a particular military doctrine, one where most casualties were not inflicted by tanks or planes, but by distant cannons. While the game’s airborne units are flashy and threatening, it’s the roving fields of fire that shape this battlefield.

That, too, strikes me as the proper way to consider GHQ. Vonnegut’s antiwar stance crystallized as U.S. involvement deepened in Vietnam, and it’s natural to wonder if the older Vonnegut set aside GHQ not only out of disappointment with Saalfield’s lack of interest but also because its maneuvers and bombardments cut too close to the bone.

It’s impossible to separate the man from the art in this case. I can’t help but view this game as not only part of Vonnegut’s journey toward his rejection of warfare and wartime thinking, but also as a way for him to turn his knowledge and experience from wartime into something productive (and profitable) for his family.

It’s pragmatic, transformative, and a little bit sad in a way that feels so keenly Vonnegut.

I haven’t had a chance to play it yet, but I do have a Barnes & Noble gift card burning a hole in my pocket, so perhaps you’ll see a more thorough writeup on GHQ in the future.

In the meantime, what do you think of this curious discovery, fellow puzzlers? Does GHQ intrigue either the reader or the tactical gamer in you? Let us know in the comments section below. We’d love to hear from you!