[Image courtesy of NSA.gov.]

The National Security Agency has been in the news a lot over the last few years.

It arguably all started with Edward Snowden and the revelations about government surveillance, both domestic and foreign, that emerged in his wake. Between President Trump’s intimations of Obama-era wiretapping (which also supposedly involved England’s GCHQ) and recent news stories about NSA contractor Reality Winner leaking information, the NSA continues to draw mainstream attention in the 24-hour news cycle.

When you factor in the declassification of codebreaking intel during and after World War II, we know more about the NSA’s inner workings than ever before.

You might be asking what the NSA has to do with puzzles. Well, everything. Because the NSA was born as a codecracking organization.

The NSA was founded in November of 1952, but its formative stages began during World War II, as codebreakers were recruited in the U.S. starting in 1943. Not only were they tasked with tackling the German ENIGMA code, but their secondary mission was to solve “the Russian problem.” This group was known as Signals Intelligence, or SIGINT.

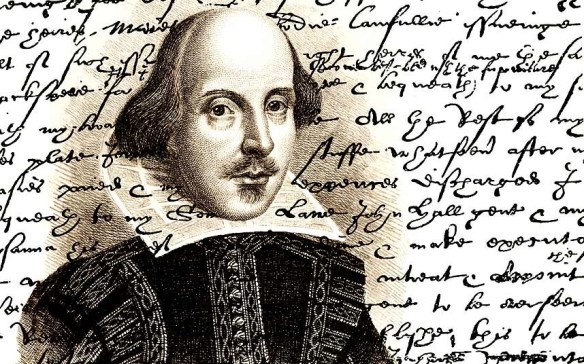

William Friedman, one of the early figures in American codebreaking, described cryptanalysis as “a unique profession, demanding a peculiar kind of puzzle-solving mentality combined with patience. So staffing this new organization was a curious endeavor.”

Those who were recruited came from all walks of life:

Career officers and new draftees, young women math majors just out of Smith or Vassar, partners of white-shoe New York law firms, electrical engineers from MIT, the entire ship’s band from the battleship California after it was torpedoed by the Japanese in the attack on Pearl Harbor, winners of puzzle competitions, radio hobbyists, farm boys from Wisconsin, world-traveling ex-missionaries, and one of the World’s foremost experts on the cuneiform tablets of ancient Assyria.

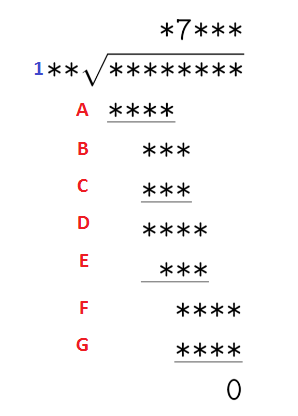

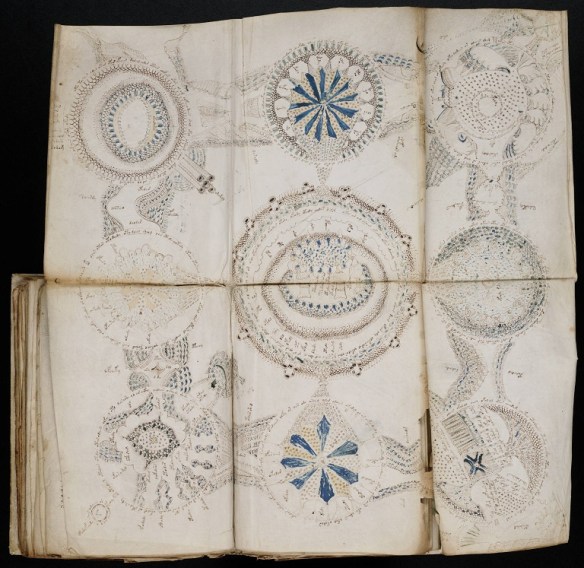

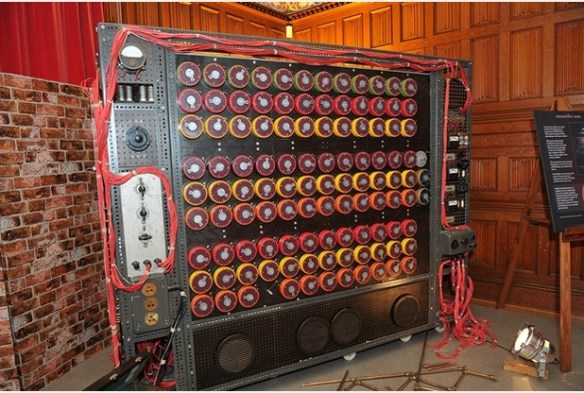

A large campus was built that echoed the style and efforts of Britain’s Bletchley Park, including Alan Turing’s calculating machines, the bombes. Efforts on both sides of the Atlantic centered on cracking ENIGMA, the German codes used in all sorts of high-level communications. The teams worked alongside the bombes to try to determine which of the 456, 976 possible codes was being used in a given piece of communication.

It was a truly Herculean effort.

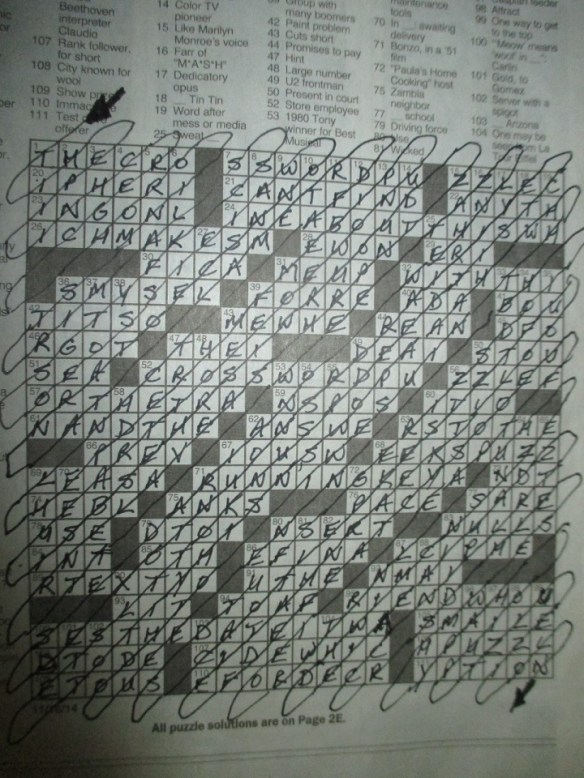

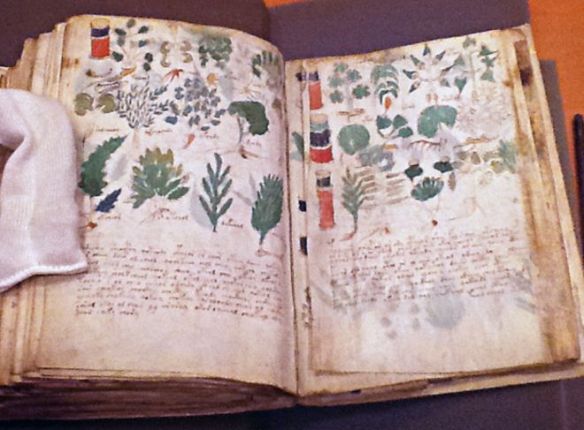

But while nearly half the staff focused on the Germans, others focused on cracking Russian codebooks, where words were translated into four-digit codes. Often, decrypting these codes involved “brute force” efforts, poring through numerous messages to pair up messages that used similar numerical groups, meaning they used the same cipher.

This would only work if the Soviets were lazy in their production of so-called “one-time pads,” encryption devices that had a particular code, which would be used once and then thrown away. Brute force codebreaking revealed that some of the one-time pads had been used more than once, a lapse in Soviet security that could work to the advantage of U.S. intelligence.

That deduction led to another stunning discovery: cracking the system used in encrypted messages to tell agents which encryption was used in a given missive. You see, each encoded message contained within it a code that dictated the cipher necessary to decrypt the message.

The Russians would later complicate this work by employing multiplexers: devices that would transmit numerous messages at once, making it harder to separate one message from another in the same dispatch.

[Image courtesy of Virtantiq.com.]

The Germans would unwittingly aid the US in their Russian codebreaking efforts when a POW camp in Bad Aibling, Germany, was captured by the US army, and they uncovered a German device designed to “de-multiplex” Russian messages. The device was called the HMFS, because Hartmehrfachfernschreiber, while a great deal of fun to type, is hard to say quickly.

After World War II ended, U.S. intelligence consolidated their efforts on “the Russian problem,” continuing their work unraveling the Russian codebooks. Slowly, the codemasters began determining which organizations in the Soviet government used which codes. Even if the codes weren’t broken yet, it helped the intelligence community organize and prioritize their efforts.

The problem? They had a very tight timeframe to work in. Those duplicated codebooks were produced during a very small window of time in 1942, and only issued to Soviet agents in the three years that followed. By 1947, SIGINT analysts knew the Soviets would soon run out of the duplicated pads. Once they did, those recurring patterns of encrypted numbers would stop, and the best chance for cracking the Soviet codes would be lost.

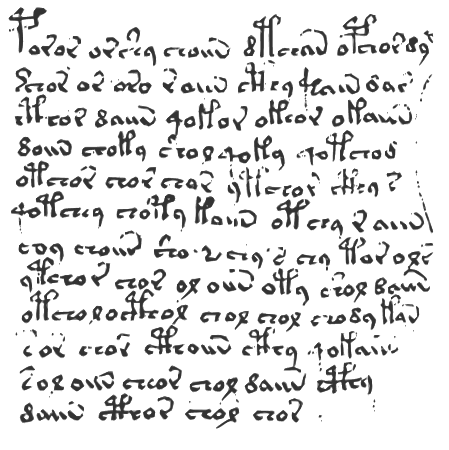

Still, there was reason to be encouraged. Some important code words had been identified. TYRE was New York City, SIDON was London, and CARTHAGE was Washington; ENORMOZ appeared often enough that they determined it referred to atomic bomb research in Los Alamos.

It would also be revealed, through careful analysis of decrypted intel, that Soviet agents were embedded in both the U.S. Justice Department and in England’s Bletchley Park campus. The Justice Department agent was identified and tried, but released after the court found insufficient evidence to place her under surveillance in the first place.

This was one consequence of the secrecy surrounding codebreaking: an unwillingness to reveal their codebreaking success by turning over evidence of it. (As for the Bletchley Park spies, one was identified in 1951 and confessed in 1964. The other was never identified.)

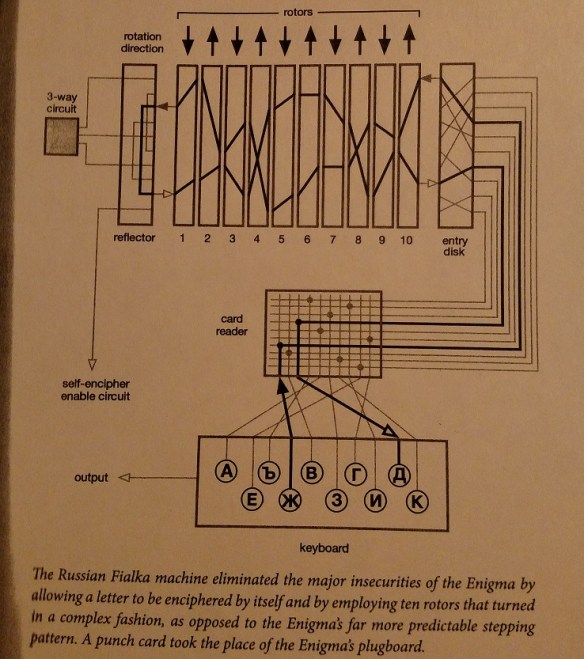

By this time, the Russians had gone over ENIGMA machines captured during the German retreat, and had unraveled not only how the devices worked, but how to improve upon them. This would lead to the next-generation Russian Fialka machine.

With ever-increasing complexity when it came to encryption, thanks to increased automation, codebreaking evolved into not just intelligence work, but intelligence analysis. After all, if you don’t know something is important, you don’t necessarily give it the attention it deserves. As researcher Stephen Budiansky put it, “The top translators at Bletchley were intelligence officers first, who sifted myriad pieces to assemble an insightful whole.”

It also led to bigger, faster machines, like Goldberg and Demon, two computation machines designed to more efficiently pore over the vast amount of encrypted information being intercepted by the various U.S. intelligence services.

In 1948, though, the game changed. It changed so dramatically that November 1, 1948, is still remembered in NSA circles as Black Friday.

I hope you’re enjoying this look at the early days of America’s codebreaking efforts. Part 2 will continue next week, with a look at the rise of the NSA, Cold War cryptography, and more!

[Quotes and certain photos were sourced from Code Warriors: NSA’s Codebreakers and the Secret Intelligence War Against the Soviet Union by Stephen Budiansky.]

Thanks for visiting PuzzleNation Blog today! Be sure to sign up for our newsletter to stay up-to-date on everything PuzzleNation!

You can also share your pictures with us on Instagram, friend us on Facebook, check us out on Twitter, Pinterest, and Tumblr, and explore the always-expanding library of PuzzleNation apps and games on our website!