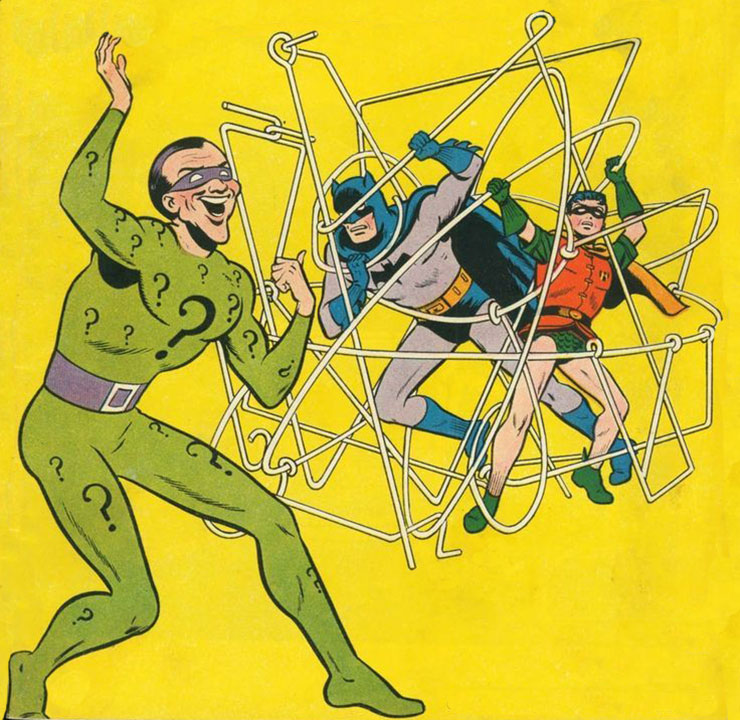

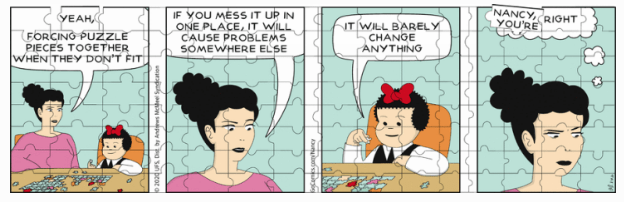

A lot can happen inside a series of squares. An Oscar-winning actor might meet a basketball star, or your favorite song might intersect with the punny punchline of a joke. Gimmicky grid construction might reveal hidden gems! Gotham might be saved from the Riddler’s clutches! Calvin and Hobbes might sculpt an army of gruesome snowmen! Krazy Kat might introduce newspaper readers to gender fluidity! You might discover new facets of your own artistic voice!

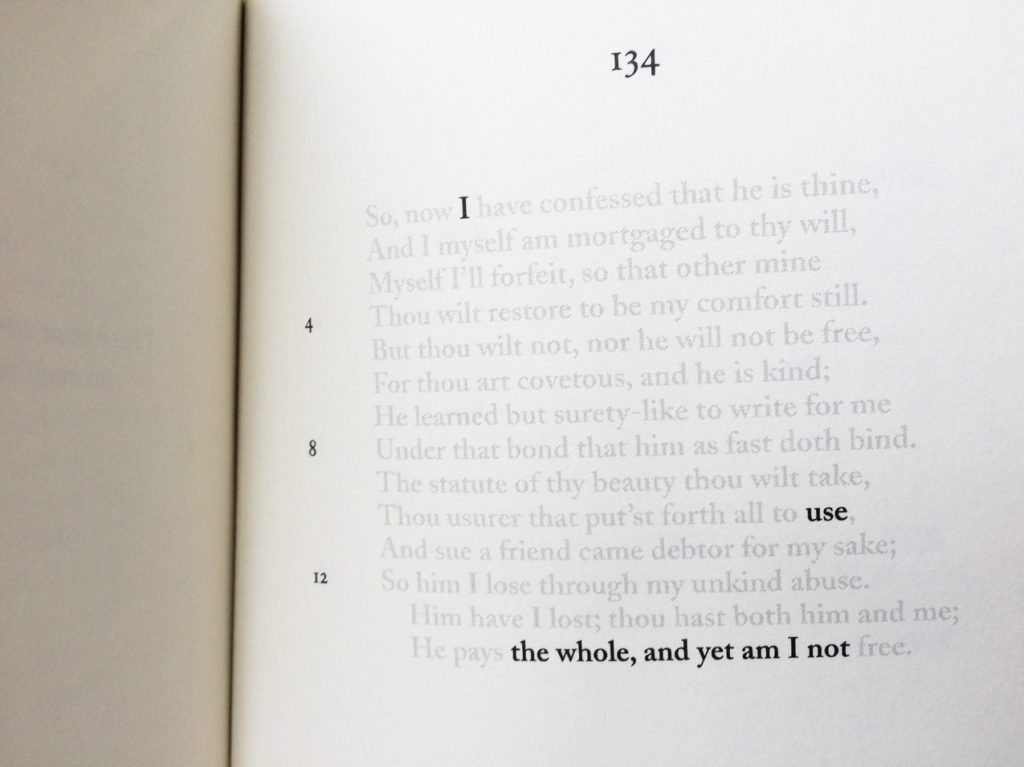

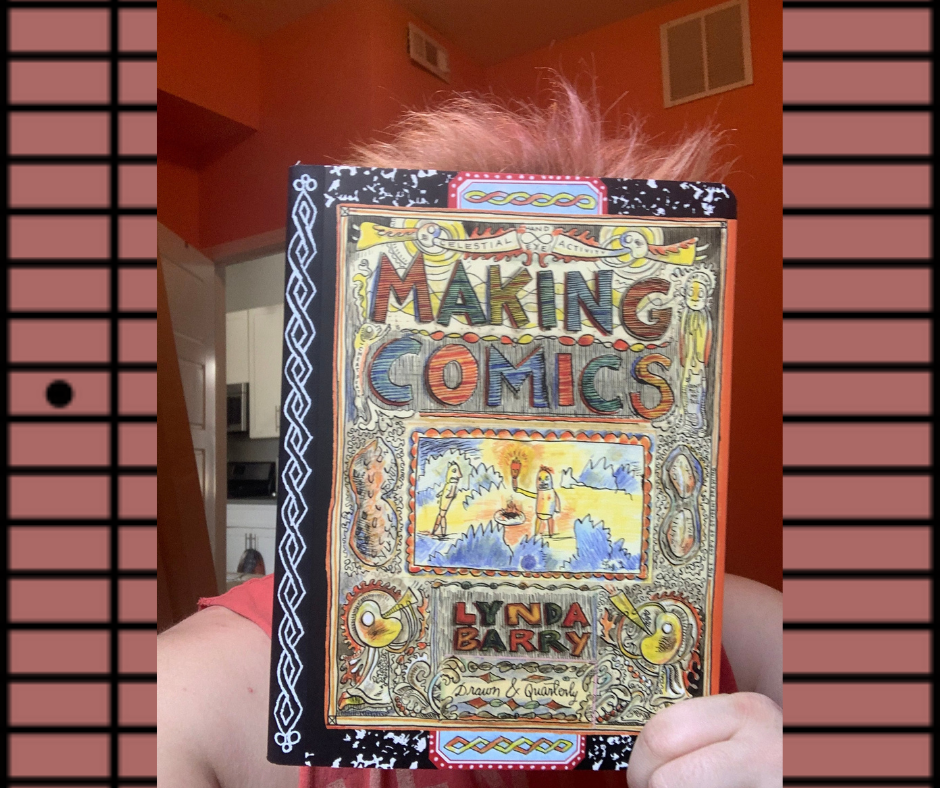

There’s a good chance you already fill in creative arrangements of squares on a regular basis, enriching your brain’s language centers by solving crosswords. Why not take this ritual a step further? Lynda Barry’s Making Comics begins with the reminder, “There was a time when drawing and writing were not separated for you,” and she shows us that it is possible to return to such a time. By partaking in the book’s exercises, you can learn to reunite images and language in your mind, to “practice the language of the image world.”

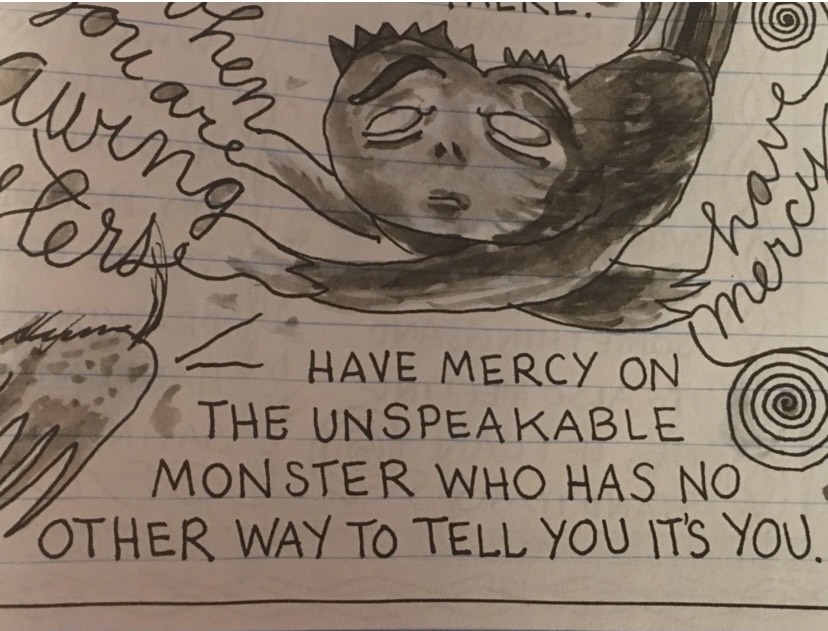

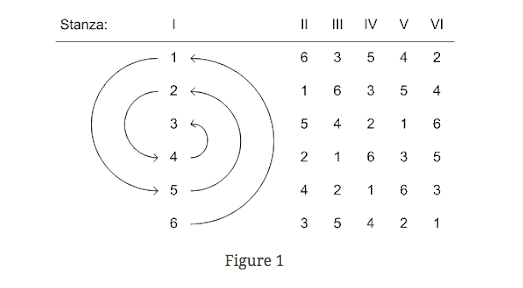

If you feel like your language centers need a good jolt, comic-making might be a perfect new hobby, and Making Comics is the perfect introductory text for puzzle fans. As Barry explains, the book’s exercises “take advantage of a basic human inclination to find patterns and meaning in random information,” and who loves patterns more than puzzlers? For instance, one simple exercise she says that anyone can do is drawing a scribble and then figuring out how to turn it into a monster. It’s that simple.

Many of the pattern-finding exercises in Making Comics’ treasure trove are collaborative, depending on a classroom setting or simply a creative partnership among friends. Others, however, can be done in solitude, including the exercises I’m going to take you through below. To prepare: Barry recommends, when just starting out, working with black Flair pens, a composition notebook (preferably not made from recycled materials), index cards (blank on one side), and basic 8.5×11 printer paper. She describes the composition notebook as “a place rather than a thing,” and says that you should try to keep it by your side like a faithful dog. “Making comics involves the same daily practice that learning any language does,” so keeping your materials handy is crucial.

Do you have your materials? Great! Let’s dive into the Animal Diary and consequent Animal Ad Lib, instructions pictured below!

More of Barry’s comics wisdom can be found on her Tumblr and Instagram, or of course, if you’re hooked, you can always pick up a copy of the book. It’s a full immersion course in a new language, in a new way of seeing.

For more fun, daily forays into the world of language, there’s Daily POP!

You can find delightful deals on puzzles on the Home Screen for Daily POP Crosswords and Daily POP Word Search. Check them out!

Thanks for visiting PuzzleNation Blog today! Be sure to sign up for our newsletter to stay up-to-date on everything PuzzleNation!